I don't have a large collection of dating sims, but I do have a sizable collection of excuses for owning any at all. “I’m trying to broaden my gaming horizons!” “It’s considered a classic in Japan!” “No, seriously, it’s for research!” “This one doesn't even have any naughty scenes!”

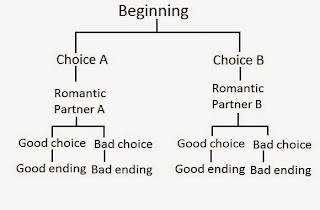

Despite the stigma attached to dating sims, I would guess that most of us are familiar with the basic concept. The player reads a story and makes decisions that branch off into multiple story paths. These story paths involve pursuing a romantic partner - going on dates, learning about their interests, etc. The "gameplay," such as it is, is limited to reading text (with pictures and music) and choosing dialogue options from a list like the following:

A). “I have always loved you.”

B). “I have always loved your best friend. Can you set us up?”

Choice A will lead to a romantic scenario with one character and choice B will lead to a different romantic scenario with another.

|

| Figure One: Branching paths |

Once the player has started down a particular story path, they must make further choices. Some options are “good,” in that the computer characters react to them positively and some are “bad,” in that the computer characters react to them negatively. Through reading the story and learning about their romantic targets, the player learns to anticipate what they want to hear. Good choices lead to good endings, bad choices lead to bad endings.

For example:

A). “I love dogs too!”

B). “I love hunting dogs!”

Choice A leads to a good ending, where you bond over a mutual love of canines, fall in love, and live happily ever after. Choice B leads to a bad ending, where your canine-hunting hobby means you die loveless and alone (which you deserve, you dog murderer).

|

| Figure Two: Multiple endings |

One of the effects of this system is that players must play the game multiple times in order to access all of the content. Choosing romantic target A usually precludes experiencing romantic target B’s story. The player must intentionally make different choices on each playthrough in order to see every ending and get the maximum content bang for their purchase buck.

|

| Figure Three: Multiple Playthroughs |

Up to this point, we have been representing the branching story paths solely as exclusive straight lines. However, this is often not the case. Many dating sims combine branching story path with a point system. For example, let’s say that a given dialogue branch has three options:

A). “You look beautiful in that skirt.” (+2)

B). “You’re pretty.” (+1)

C). “What, was your nice mumu in the wash?” (-1)

The story proceeds based on how many points the player has accumulated with each target, not simply off of binary branching paths. These points are generally not visible to the player, but rather inferred through the computer characters’ reactions. For example:

A). “Your eyes are like limpid pools of starlight from the summer evenings of my youth.”

Response: “Oh my! *swoon*

B). “You’ve got pretty eyes.”

Response: “Uh, thanks?”

C: “Wow! Your eye boogers are huge!”

Response: “Get away from me!”

Not all choices in the game award the player with points. For example, choosing to visit the library may not get you any points, but it will give you a chance to interact with Romantic Partner A (whereas visiting the pool lets you meet with Romantic Partner B). The player can leverage information to find these events – “Oh, A likes reading, so I should go to the library.”

This score is influenced by things other than dialogue choices. Some games allow the player to give gifts that increase points, some have mini-games, and so on. The game’s ending is determined not only by which branch of the story you follow, but also by how many points you have.

|

| Figure Five: Point system |

Even taking points into account, the player only has two resources to manage: information and choices. Through reading the story and paying attention to the object of their affection, the player is able to make choices that move the story in the desired direction.

That's the basic structure. Now let's complicate it.

Sentimental Graffiti has most of the standard features of a dating sim. There are multiple romantic interests, you make dialogue choices, and the story progresses based off of how many points you accumulate. However, the story never truly branches - the best ending can only be received by jugglingi all of the romantic partners.

The protagonist is a Tokyo high school student who moved to twelve cities around Japan in his early childhood. During this time, he met twelve girls with whom he formed a special relationship (surprisingly, this in not a euphemism). One day, he receives an unsigned letter that simply says "I want to meet you." He believes this letter came from one of the twelve girls, and so he embarks on a quest to figure out which one sent it.

Because these girls live all across Japan and the protagonist is still a student, Sentimental Graffiti is as much of a resource management game as a dating sim. He can only travel to meet them on weekends and holidays, and travelling requires the expenditure of time, money, and energy. The player has to balance these resources to maintain relationships with twelve girls in twelve different cities in order to achieve the best ending.

|

| Traveling costs time, money, and energy

AKA, Waifus in different area codes

|

The player can telephone the girls to set up dates for a specific day and time in advance, which requires carefully constructing elaborate travel plans. A poorly planned three-day weekend involves crisscrossing the country multiple times and can leave you too broke to travel the next weekend. Finding yourself stuck in Hiroshima when you need to be in Sapporo in five hours is a nasty experience.

The mystery letter also complicates the usual dating sim formula. The protagonist's motivation is not the search for true love, but rather figuring out which girl sent the letter. Why he leads them on with months of dating instead of just asking them if they sent the letter (or asking for a handwriting sample) is perhaps a greater mystery.

|

| Seriously, just check the handwriting! |

At any rate, my original plan was to meet all of the girls once and then follow up the ones I thought were most likely to have sent the letter. Imagine my surprise when the eight I decided to give up on started leaving me passive-aggressive voice messages. At first they complained that I wasn't meeting them, but then they just started leaving silent voice messages. This went on for months of in-game time.

|

| I saw a lot of this dialogue box |

Finally, I got tired of the silent voice messages and called them back. Their family members informed me that they were so broken up over not dating me that they ran away from home/fell in with a bad crowd/gave up on life. Remember, this is after meeting them one time after years of no contact.

|

| Oh faceless protagonist, you heart-breaking cad. |

This was something that I had truly not planned for. I can work out train schedules and finances, but there's just no anticipating insanity/the deeply misogynistic attitudes of Japanese game developers.

Ultimately, I enjoyed the resource management aspect of Sentimental Graffiti more than the story. It was an interesting twist on the standard game mechanics of the genre, but figuring out how I was going to get places was more interesting than what happened once I arrived. Between the mercenary protagonist and the all-too-eager girls, it seemed less of a dating sim and more of a cautionary tale about codependence.