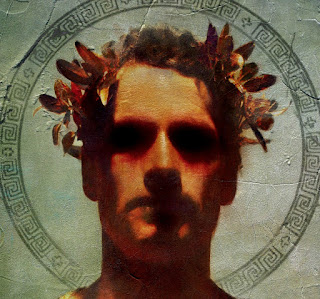

Handlug

Vs. Tat

While

most are familiar with Freud’s take on the story, Freud is not the only game in

town. Hegel uses the story of Oedipus to illustrate the difference between what

he terms handlug and tat (if you thought I would pass up a chance to talk about Hegel, prepare to be disappointed).

Handlug

is the intended action while tat is the actual result. For example,

let’s say that I pick up what I think is a delicious peanut butter and jelly

sandwich and take a bite, only to find a tarantula inside. My intended

action is eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich (handlug). However,

my actual action is eating a peanut butter and jelly and tarantula

sandwich (tat) because, unknown to me, a big hairy spider has crawled

between the slices of bread. I intended to do one thing, but another

thing actually happened.

Oedipus’

handlugs are meant to escape his

prophesied destiny: killing a belligerent old man as he flees his Corinthian

“father,” saving a kingdom, and marrying a queen instead of his Corinthian

“mother.” His tats fulfill the

prophecy: killing his true father, marrying his true mother, and thus bringing

down the curse of the gods on the kingdom of Thebes.

Handlug

|

Tat

|

Escape the

prophecy

|

Fulfilled

the prophecy

|

Kill a

belligerent old man

|

Killed his

father

|

Save a

kingdom

|

Cursed a

kingdom

|

Marry a

queen

|

Married his

mother

|

It

bears pointing out that Oedipal morality is still binary – Oedipus is horrified

at what he has done, as are the gods. Patricide and incest are evil, abominable

things, things which cannot be forgiven by the excuse that Oedipus did not know

what he was doing. The important point is not what Oedipus intended to do, but what he actually

did.

Hegel

refers to this as “heroic morality,” wherein the moral actor takes

responsibility for the results of action regardless of the intention behind

them. It does not matter to my taste buds whether I intended to eat a peanut

butter and jelly and tarantula sandwich or not. Whatever my intentions, the

results are the same.

This

sort of thinking was popular among the Greeks, but we can also see traces of it

in the Old Testament kosher laws. It does not matter whether or not I intended

to touch a dead body (or to be born crippled, or to menstruate); I am rendered

impure by actuality, not intent (In defense of old Yahweh, there is evidence this only applies to ritual impurity and not moral impurity - Jeremiah, for one, posits that it is possible to obey all of the ritual obligations and still be morally impure.)

But

there are also key differences between heroic morality and the Garden of Eden.

Eve’s choices are explicitly labeled and lead to predictable results while

Oedipus’ choices have their “labels” switched. Leaving Corinth seemed like the

good choice that would lead him away from evil but ended up leading to his

downfall. Yahweh's fruit quiz seems positively sporting in comparison.

This

same difference exists when we compare Pandora and Oedipus. Pandora acts

consciously and in line with her desires – the gods may be setting her up, but

she wants to open the jar. Oedipus,

on the other hand, acts completely out of line with his desires. He is

consciously striving to avoid evil, to the point of leaving behind the only

home he has ever known.

There

are, of course, overlaps between Pandora and Oedipus. Oedipus exists in a world

of fate, where he is destined to commit certain actions no matter how far he

runs. We can still argue that Oedipus is being pushed, but Sophocles also uses

the story to explore deeper moral dimensions. What is the difference between

intended action and actual action? Are we responsible for who we are on the

inside or what we do on the outside?

And this is the

essential difference between Pandora and Oedipus. The story of Pandora is the

story of an action. The story of Oedipus is a story about action.

Next: [OE010] The Game Mechanic: Your Precious Eyes